Notes - TCP Congestion Control

The following notes have been made with reference to the book Computer Networking A Top Down Approach by Kurose and Ross. Content has been quoted from the book. All credits to the author.

- TCP provides a reliable transport service between two processes running on different hosts.

- Another key component of TCP is its congestion-control mechanism. TCP must use end-to-end congestion control rather than network-assisted congestion control, since the IP layer provides no explicit feedback to the end systems regarding network congestion.

- The approach taken by TCP is to have each sender limit the rate at which it sends traffic into its connection as a function of perceived network congestion. If a TCP sender perceives that there is little congestion on the path between itself and the destination, then the TCP sender increases its send rate; if the sender perceives that there is congestion along the path, then the sender reduces its send rate.

- But this approach raises three questions.

- First, how does a TCP sender limit the rate at which it sends traffic into its connection?

- A TCP connection consists of a receive buffer, a send buffer, and several variables (LastByteRead, rwnd, etc). The TCP congestion-control mechanism operating at the sender keeps track of an additional variable, the congestion window.

- Congestion Window (cwnd) is a TCP state variable that limits the amount of data the TCP can send into the network before receiving an ACK. The Receiver Window (rwnd) is a variable that advertises the amount of data that the destination side can receive. Together, the two variables are used to regulate data flow in TCP connections, minimize congestion, and improve network performance.

- Specifically, the amount of unacknowledged data at a sender may not exceed the minimum of cwnd and rwnd (receiver window), that is :

LastByteSent - LastByteAcked <= min{cwnd, rwnd} - Assumptions made henceforth: The TCP receive buffer is so large that the receive-window constraint can be ignored; thus, the amount of unacknowledged data at the sender is solely limited by cwnd. We will also assume that the sender always has data to send, i.e., that all segments in the congestion window are sent.

- The constraint above limits the amount of unacknowledged data at the sender and therefore indirectly limits the sender’s send rate. At the beginning of every RTT, the constraint permits the sender to send cwnd bytes of data into the connection; at the end of the RTT the sender receives acknowledgments for the data. Thus the sender’s send rate is roughly

cwnd/RTTbytes/sec. By adjusting the value of cwnd, the sender can therefore adjust the rate at which it sends data into its connection.

- Second, how does a TCP sender perceive that there is congestion on the path between itself and the destination?

- Let us define a “loss event” at a TCP sender as the occurrence of either a timeout or the receipt of three duplicate ACKs from the receiver.

- When there is excessive congestion, then one (or more) router buffers along the path overflows, causing a datagram (containing a TCP segment) to be dropped. The dropped datagram, in turn, results in a loss event at the sender—either a timeout or the receipt of three duplicate ACKs—which is taken by the sender to be an indication of congestion on the sender-to-receiver path.

- When the network is congestion-free, that is, when a loss event doesn’t occur. In this case, acknowledgments for previously unacknowledged segments will be received at the TCP sender. As we’ll see, TCP will take the arrival of these acknowledgments as an indication that all is well—that segments being transmitted into the network are being successfully delivered to the destination—and will use acknowledgments to increase its congestion window size (and hence its transmission rate).

- Note that if acknowledgments arrive at a relatively slow rate, then the congestion window will be increased at a relatively slow rate. On the other hand, if acknowledgments arrive at a high rate, then the congestion window will be increased more quickly. Because TCP uses acknowledgments to trigger (or clock) its increase in congestion window size, TCP is said to be self-clocking.

- Third, what algorithm should the sender use to change its send rate as a function of perceived end-to-end congestion?

- How then do the TCP senders determine their sending rates such that they don’t congest the network but at the same time make use of all the available bandwidth? Are TCP senders explicitly coordinated, or is there a distributed approach in which the TCP senders can set their sending rates based only on local information? TCP answers these questions using the following guiding principles:

- A lost segment implies congestion, and hence, the TCP sender’s rate should be decreased when a segment is lost. A timeout event or the receipt of four acknowledgments for a given segment (one original ACK and then three duplicate ACKs) is interpreted as an implicit “loss event” indication of the segment following the quadruply ACKed segment, triggering a retransmission of the lost segment. From a congestion control standpoint, the question is how the TCP sender should decrease its congestion window size, and hence its sending rate, in response to this inferred loss event.

- An acknowledged segment indicates that the network is delivering the sender’s segments to the receiver, and hence, the sender’s rate can be increased when an ACK arrives for a previously unacknowledged segment.

- Bandwidth probing. Given ACKs indicating a congestion-free source-to-destination path and loss events indicating a congested path, TCP’s strategy for adjusting its transmission rate is to increase its rate in response to arriving ACKs until a loss event occurs, at which point, the transmission rate is decreased. The TCP sender thus increases its transmission rate to probe for the rate that at which congestion onset begins, backs off from that rate, and then to begins probing again to see if the congestion onset rate has changed. Note that there is no explicit signaling of congestion state by the network—ACKs and loss events serve as implicit signals—and that each TCP sender acts on local information asynchronously from other TCP senders.

- How then do the TCP senders determine their sending rates such that they don’t congest the network but at the same time make use of all the available bandwidth? Are TCP senders explicitly coordinated, or is there a distributed approach in which the TCP senders can set their sending rates based only on local information? TCP answers these questions using the following guiding principles:

- First, how does a TCP sender limit the rate at which it sends traffic into its connection?

TCP congestion-control algorithm

- The algorithm has three major components: (1) slow start, (2) congestion avoidance, and (3) fast recovery.

- Slow start and congestion avoidance are mandatory components of TCP, differing in how they increase the size of cwnd in response to received ACKs. Slow start increases the size of cwnd more rapidly (despite its name!) than congestion avoidance.

- Fast recovery is recommended, but not required, for TCP senders.

Slow Start

- When a TCP connection begins, the value of cwnd is typically initialized to a small value of 1 MSS (Maximum Segment Size), resulting in an initial sending rate of roughly

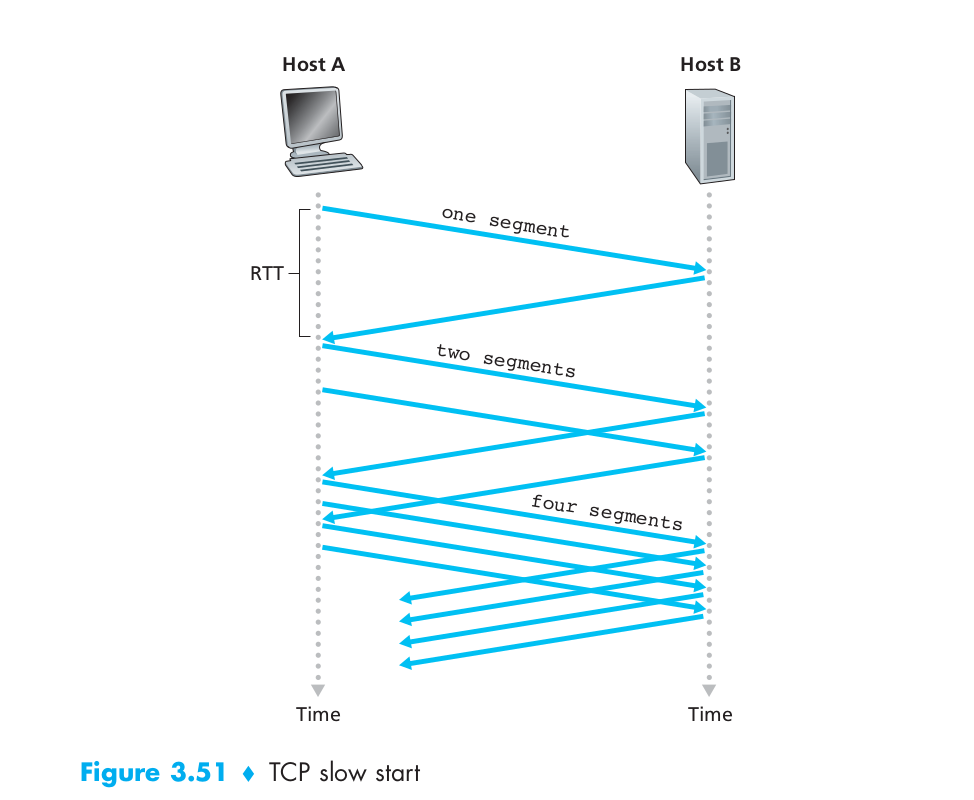

MSS/RTT. - Since the available bandwidth to the TCP sender may be much larger than MSS/RTT, the TCP sender would like to find the amount of available bandwidth quickly. Thus, in the slow-start state, the value of cwnd begins at 1 MSS and increases by 1 MSS every time a transmitted segment is first acknowledged.

- This process results in a doubling of the sending rate every RTT. Thus, the TCP send rate starts slow but grows exponentially during the slow start phase.

- But when should this exponential growth end? Slow start provides several answers to this question.

- First, if there is a loss event (i.e., congestion) indicated by a timeout, the TCP sender sets the value of cwnd to 1 and begins the slow start process anew. It also sets the value of a second state variable,

ssthresh(shorthand for “slow start threshold”) tocwnd/2— half of the value of the congestion window value when congestion was detected. - The second way in which slow start may end is directly tied to the value of ssthresh. Since ssthresh is half the value of cwnd when congestion was last detected, it might be a bit reckless to keep doubling cwnd when it reaches or surpasses the value of ssthresh. Thus, when the value of cwnd equals ssthresh, slow start ends and TCP transitions into congestion avoidance mode. TCP increases cwnd more cautiously when in congestion-avoidance mode.

- The final way in which slow start can end is if three duplicate ACKs are detected, in which case TCP performs a fast retransmit and enters the fast recovery state.

- First, if there is a loss event (i.e., congestion) indicated by a timeout, the TCP sender sets the value of cwnd to 1 and begins the slow start process anew. It also sets the value of a second state variable,

Congestion Avoidance

- On entry to the congestion-avoidance state, the value of cwnd is approximately half its value when congestion was last encountered.

- Thus, rather than doubling the value of cwnd every RTT, TCP adopts a more conservative approach and increases the value of cwnd by just a single MSS every RTT.

- This can be accomplished in several ways. A common approach is for the TCP sender to increase cwnd by MSS bytes (MSS/cwnd) whenever a new acknowledgment arrives. For example, if MSS is 1,460 bytes and cwnd is 14,600 bytes, then 10 segments are being sent within an RTT. Each arriving ACK (assuming one ACK per segment) increases the congestion window size by 1/10 MSS, and thus, the value of the congestion window will have increased by one MSS after ACKs when all 10 segments have been received.

- But when should congestion avoidance’s linear increase (of 1 MSS per RTT) end? TCP’s congestion-avoidance algorithm behaves the same when a timeout occurs. As in the case of slow start: The value of cwnd is set to 1 MSS, and the value of ssthresh is updated to half the value of cwnd when the loss event occurred.

- Recall, however, that a loss event also can be triggered by a triple duplicate ACK event. In this case, the network is continuing to deliver segments from sender to receiver (as indicated by the receipt of duplicate ACKs). So TCP’s behavior to this type of loss event should be less drastic than with a timeout-indicated loss: TCP halves the value of cwnd (adding in 3 MSS for good measure to account for the triple duplicate ACKs received) and records the value of ssthresh to be half the value of cwnd when the triple duplicate ACKs were received. The fast-recovery state is then entered.

Fast Recovery

- In fast recovery, the value of cwnd is increased by 1 MSS for every duplicate ACK received for the missing segment that caused TCP to enter the fast-recovery state.

- Eventually, when an ACK arrives for the missing segment, TCP enters the congestion-avoidance state after deflating cwnd.

- If a timeout event occurs, fast recovery transitions to the slow-start state after performing the same actions as in slow start and congestion avoidance: The value of cwnd is set to 1 MSS, and the value of ssthresh is set to half the value of cwnd when the loss event occurred.

- Fast recovery is a recommended, but not required, component of TCP.

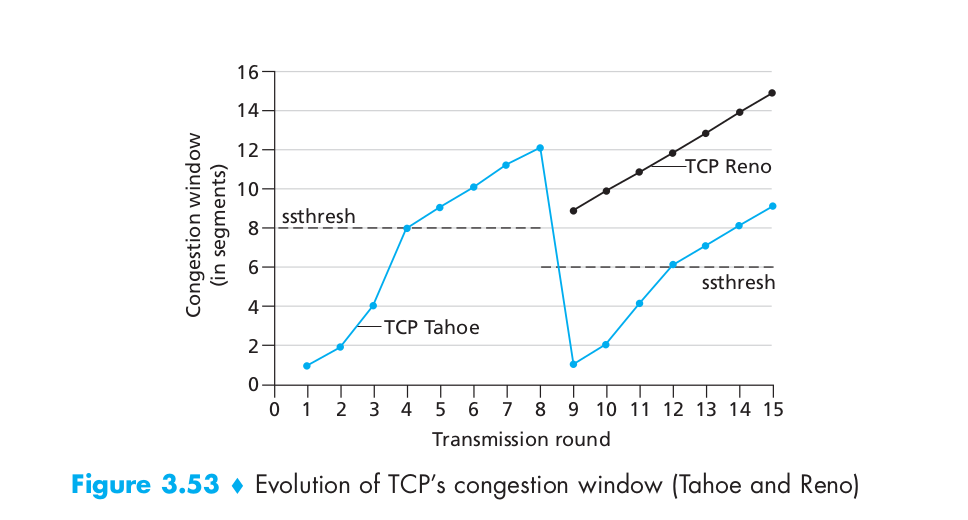

- It is interesting that an early version of TCP, known as TCP Tahoe, unconditionally cut its congestion window to 1 MSS and entered the slow-start phase after either a timeout-indicated or triple-duplicate-ACK-indicated loss event. The newer version of TCP, TCP Reno, incorporated fast recovery.

- In this figure, the threshold is initially equal to 8 MSS. For the first eight transmission rounds, Tahoe and Reno take identical actions. The congestion window climbs exponentially fast during slow start and hits the threshold at the fourth round of transmission. The congestion window then climbs linearly until a triple duplicate ACK event occurs, just after transmission round 8. Note that the congestion window is 12 MSS when this loss event occurs. The value of ssthresh is then set to 0.5 * cwnd = 6 MSS.

- Under TCP Reno, the congestion window is set to cwnd = 6 MSS and then grows linearly.

- Under TCP Tahoe, the congestion window is set to 1 MSS and grows exponentially until it reaches the value of ssthresh, at which point it grows linearly.

Other References

This post is licensed under CC BY 4.0 by the author.